I’ll confess, I was in a dour mood when I first started to draft this post a few days ago, not fully sure why. But it was the perfect timing to scour through my photos of my time in Poland, to supply this first recap post. Seeing the people, above all, brought me back to the best of those times, and the dour mood went away. I’ll be a little photo-heavy here, and go through the time I arrived in Poland a few weeks before Thanksgiving, all the way to early January.

I will also advise, warn, what have you, that after a lot of pleasant photos and stories of the work we did, I have included photos of my time at Auschwitz Museum (built on and in the complex of Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp) and text describing them, and giving them historical context.

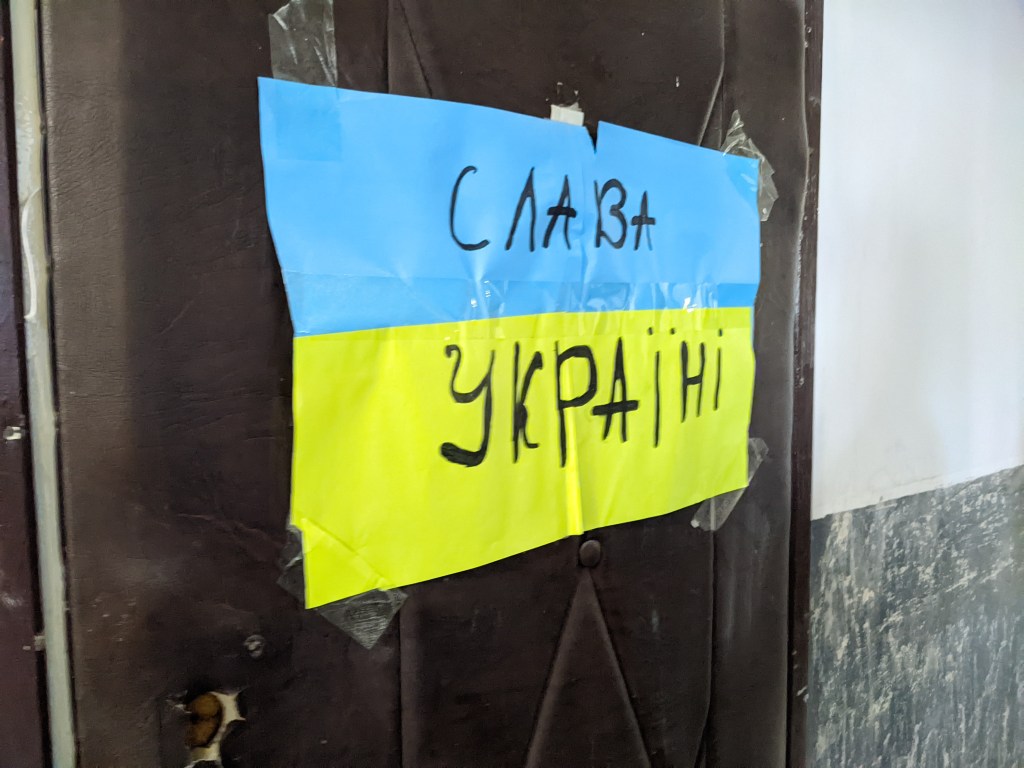

These are two very different blog posts put in one, because in the end I felt they are connected. The horrors of mobile crematoria that Russia brought with it into Ukraine (with hopeful plans to purge Ukrainian society of those who would resist occupation), the brutality of its massacres of Ukrainians in Bucha, are all echoes of Hitler’s playbook, or better put, the universal playbook of humankind twisted by extremism and greed.

I came to Poland precisely because I was aware of these historical parallels. The happy stories of what we did stands in contrast, yin and yang, to the horrors of what happened when people did not act fast enough. Our actions were one very tiny part of a response, that has included the critical military and financial aid that many governments and countless individuals have given to Ukraine- and of course, the courage of the Ukrainian resistance.

I do not want to separate the one post into two, but obviously will force no one to read anything. You will have the chance to not read the Auschwitz section, as it will be separate at the bottom. I wrote the positive part first, then the Auschwitz section, and then came back to write these warnings. The shift in tone should be understood from that perspective.

For the next while, this blog post will be a story of positivity and the good things I took part in. You will be warned and clearly advised at the start of the Auschwitz section that it will be a different kind of post from then on.

And so…the positive start (first written)…

I arrived to the city of Kraków (CRACK-oof), as the cheapest airport near to the project. Little did I know I’d be head over heels for it in short order. I could write a whole post about Kraków but won’t right now! I spent one night in it on the way in, and headed on the train to Jarosław (yarr-oh-SWAFF).

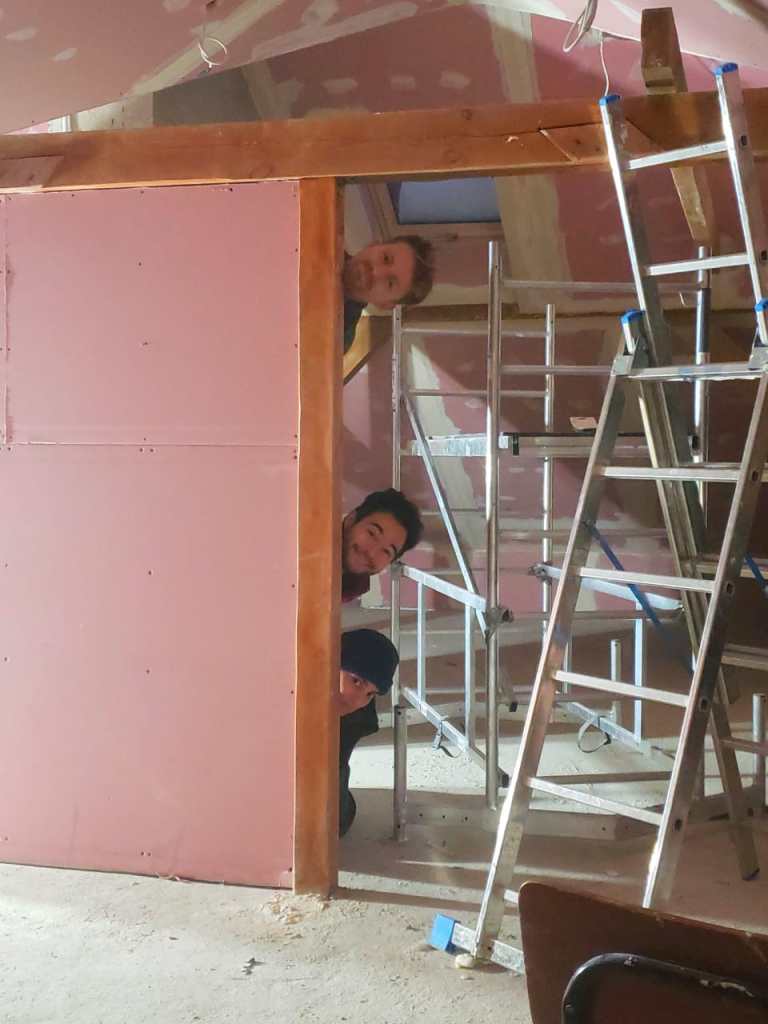

We renovated the attic space so that the building would have a communal area separate from the crowded bedrooms- it was a huge attic and took a good chunk of my time there for the first half of my stay. I did a shit ton of drywall work. Drywall is my least favorite thing in construction, I designed it out of my home so I’d never have to do it. Every time I got in the van to go to site, I thought of why I was there though.

The people who experienced the Boratyn site felt a huge attachment to it by the end- so many days put in it before it had heating, before it had light. Lots of days of seeing your breath as Polish November and December got colder and colder. Here my construction site supervisor Santiago dons the warpaint of Boratyn- the mud for the walls.

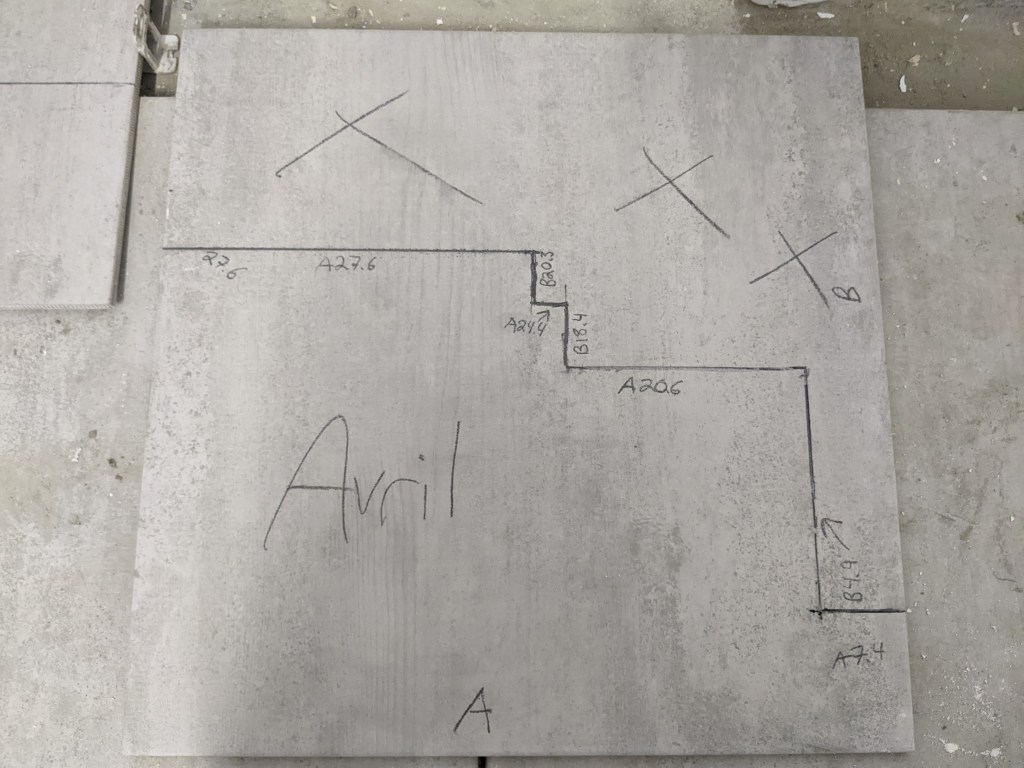

Just before Christmas, I got in on gluing the laminate floor in the space- and we had yet one more chance to explore how challenging the space was! It was an irregularly shaped attic that had challenged all of our layout skills.

I spent my first Christmas ever away from home, in Poland. It was only my second Thanksgiving I’d ever missed. I’d love to talk a bit about those holidays in Poland. Polish culture, of course, does not do Thanksgiving. It’s a North American thing. However, about 60%+ of us were norteamericanos so our base observed.

It was a powerful lesson for me- or a mini lesson reinforcing what I saw time and time again. Kind, remarkable people taking the time to care for others, and using all their faculties for it as well. The organization is All Hands and Hearts- and I thought about how we bring our physicality to our jobs, and put our bodies into uncomfortable situations- call that the Hands part. We also bring our emotions- the most visceral part of what may drive you to do the right thing, the Heart. But an additional thing is our minds- the one thing that didn’t make the name of the organization but it’s what I saw in so many people, that I tried to model myself after as well. You should ideally bring all three on every project.

It also was a model for how to treat another culture’s holidays. It was really touching for a non-American to put that thought and effort into our Thanksgiving. A few folks (both American and non) murmured things about the difficult history surrounding the holiday, but any given holiday is about what you make of it now. It’s a time to focus on gratitude, a time to be thankful for who you have around you. For Americans it’s also about just having a lot of good homey food.

We were hosted by a refugee shelter located in Przemysl, Poland, run by an American who’d bought a warehouse and turned it into an all-welcome shelter, mostly focused on 48 hour needs of getting people warm food, showers, laundry, and the chance to plan their next move, but also hosting some people with more mid term needs. Many larger shelters had a women-and-children only policy- because it takes more staffing, effort, and space, to manage divisions by gender, and the safety considerations that come from that. Other shelters also had strict 48 hour policies, so they could focus on that immediate emergency needs, but since this one was independently run, he could choose to be flexible, case by case. Other shelters also had rules that if you’d been in Ukraine more than 24 hours, you were no longer an “emergency case,” and couldn’t apply. This shelter, again being independent and small, did not worry about that- they just helped who needed help. In that regard it had become known at the train station as the place that would take the tougher cases.

All Hands installed large banks of kitchen cabinets and backsplashes for this shelter, and also simple sturdy wooden shelving for their pantry, which is how we came to know them. We did a joint Thanksgiving bringing together his volunteers, us, and an Azerbaijani family (immigrants to Ukraine) who had left together, who were the current residents at the time. It was the second strange time in my life where speaking Turkish came in handy enough to speak to Azeris. My Turkish was rusty but I was able to sit together with and connect with the family. Turkish and Azeri are like Spanish and Portuguese- quite close, yet different- but it can be made to work.

As a teaser, I’ll say that the experience of Thanksgiving in Przemysł (pSHEH-mish) drove me to a pay-it-forward moment when I was on-project in Turkey with a British-heavy group of folks, on Coronation Day. More on that at another time. It really doesn’t take much to be kind, to not make *your* view of a holiday shit on another’s enjoyment of it- or to make your hot take on a holiday interfere on another’s enjoyment of it. A lot of hands, hearts, and minds went into an excellent Thanksgiving in Przemysł, Poland.

Christmas

One thing I’d like to share about, was a valuable friendship I made at Christmas, and lessons learned from it. Also, a horrifying, embarrassing picture of me playing a parlor game is included in fairness, so I can share the others’ in good conscience.

The little story to share was about a volunteer, Maddie, who came for a 7 day slot. In her goodbye speech (a thing we all do when leaving project,) she thanked the people who’d still made the effort to know her despite her short time there. What’s funny is one of the things I’d admired most about her was the effort she’d put into improving the whole group’s Christmas, despite the shortness of her stay. First- it was remarkable that she’d come at that time. She sacrificed the options of Christmas with others but that was her only 7 day slot to come help.

Second, she organized a big round of family-style parlor games for Christmas. She was the emcee for all the games and helped make the place like home. That someone would do that effort is a testament to character. Maddie if you’re reading this- you’re pure class. Those things are how a friendship of such solidity can happen in 7 days. People meet on project and quickly find shared values and admiration for each other in short time.

She came at a particular time when I was just starting to burn out from making efforts to meet people on 7 to 14 day stays. I made efforts to try to meet everyone but that takes a toll as goodbyes start to roll around. Being one of the long-termers, you felt like an Elf in Lord of the Rings, or like a vampire- like you were immortal and all your “mortal” friends would come and go while you stayed, lingering behind. It got tiring and is still something to watch out for on projects.

I was almost, just almost, ready to stop doing it (making efforts to befriend shorter term folks) when Maddie made that comment part of her goodbye speech. It takes mental discipline to value people enough to keep up that effort-whether you’re someone coming for a short stay, or a long-termer meeting someone on a short stay, and to still value human connection enough to start a friendship.

Maddie went to the trouble to organize a series of fun games that she taught us and led us in. This particular parlor game is one called Muddy Buddy, if I remember right. You start with a chocolate-covered thing on your forehead, and without using your hands, you have to eat the treat. You contort your face muscles to safely work it down (if it falls, you’re out), and you have to hurry since melting sticky chocolate makes the job harder every second you tarry with it.

I won first point for my team. I had never trained for it but I think my genuine burning desire to eat the treat is what drove me.

Now, for my friends’ embarrassing photos to share…

Lyndsey from Alberta, quickly getting in dangerous territory with the classic trap- the human eye socket.

PS, that hoodie she brought, she threw it in the freebie bin when she left, and it kept getting passed down and inherited, and seemed to bestow its wearers with Lyndsey’s “competent boss” energy. If I were an RPG game designer, I’d say the hoodie had Intelligence, Wisdom, Dexterity, Strength, AND Charisma (ie everything) buffs for sure- a powerful talisman. It all started with Lyndsey’s propensity for training new people on tools, for training people on health and safety, and for basically knowing what was going on and what should be going on, about 101% of the time.

Final wrapup of our Christmas- we did a lazy mid morning Christmas breakfast, which included a French toast bake, scrambled eggs, bacon, salmon sausage, and empanadas. There was very little room left for bananas.

Now, back to some of the work we were doing. For the second project I was a part of*, a building in rough shape had been turned in to apartment housing due to the war. Because of the urgency of the situation, people had to move in even while only one bathroom was in use, in a building with 30-40 person occupants. It was university-dorm style, in that families each had their own rooms but walked down a hall for a shared kitchen and shared bathroom. All Hands and Hearts volunteered to install one handicap-accessible bathroom and an additional 2 regular toilets, in addition to kitchen cabinets, a kitchen floor, and repainting the hall and stairwell.

*At an All Hands project, anywhere from 3 to 7 subsites/projects may be going on at once. Most of these projects were happening at the same time, but I personally stuck on one, and then another, in work assignments.

The site had a combined challenge and blessing, compared to the Boratyn project. People were already living in it. I’ve made dear friends I still have to this day, amongst the residents there, but the project was challenging as we were doing often loud, often dirty work in the spaces they lived in. We could only shut down one bathroom at a time, while trying to get capacity up, all while kicking up dust in the halls, etc.

They were sometimes emotionally straining workdays, as we cared deeply about getting the project done quickly, and well (which can be at odds…we try to strike that balance), and with compassion for the current residents. They couldn’t have been kinder though. Despite the stress of raising kids in a foreign country, after fleeing home, they were forbearing about what we had to do in their temporary homes.

Several of them, Iryna, Yulia, and Tatiana, made us food several times. Doing so while having all their other responsibilities was really thoughtful and kind. I’ll just share three photos of when we got served the best borshch we ever had.

Meanwhile, at their apartment building, our goal was to cheaply and efficiently do a few small things that made the place a little more reasonable to be in. It wasn’t like an over-the-top Extreme Home Makeover kind of thing- it was simple things like having counter space instead of old tables- or cabinets instead of having to keep your stuff in a milkcrate or cardboard box on the floor. Wood laminate floors that didn’t steal the warmth from your feet as you stood on them. Extra bathrooms so people don’t have to wait in lines in the morning for basic hygiene.

What I see, psychologically, is that war or disaster can fundamentally throw someone’s sense of value. You can feel deeply devalued when someone is willing to launch missiles in your direction, aware it may hit you, aware that the sirens will steal you of another night’s sleep. So, this disaster work is a small act to try to reverse some of that feeling.

Here’s a few process and end result photos from this site-

Radymno

The third-to-final site I contributed to was located in the town of Radymno. It was a former mental hospital, converted to large scale refugee housing. The building had 4 levels, families could each stay in their own room. It had a wide range of stay times- some folks for a few days, others for weeks or months.

Polish contractors took pity on us sometimes- the folks who were doing some hired renovations. We had tools, but sometimes theirs were better and with a smile and nod, they’d lend us theirs or make a few cuts for us. I was about to give Avril a go until a Polish guy took it to his nice cutting setup.

The way All Hands sometimes works, is that we take on projects that an organization was about to have to use grant money for- saving them money to use for yet other projects. Other times, their money may have already been out, and we stepped in to do projects that simply wouldn’t have happened otherwise. In Radymno, they had some money for renovations, from a UN fund that was backed by the government of Japan, so we were helping them stretch their donation dollars by peeling off a few of the tiling projects that they were likely to do. Polish contractors took on some of the larger, trickier jobs in the communal bathrooms, so they were often working nearby with similar tools.

The painting was unlikely to be done, if I was able to read the discussions right, so that’s a thing we made happen due to our budget and personnel power. Painting may seem like a non priority thing, but the dingy halls with ancient, old paint recalled the building’s days as a mental institution. We repainted it to mostly bright whites, and in the hallway, bright light blue on bottom and white on tops and ceilings. There was also locations of chipping paint, or places where the mortar had crumbled, so painting was also an excuse to fix those mortaring and plastering issues.

In my mind, from what I have seen in disaster response, nothing is cosmetic. What you are doing is fundamentally communicating, through action, that you care. That can include a brighter paint color to improve the mood of the building, or making people feel a bit less like they’re in a crumbling 1980’s institutional building. It all added up and had purpose.

Part of what decides what money or time we spend on something, is thinking of its lifetime use. This kind of solution may not be what a private homeowner would do for something they’d enjoy for 20 or 30 years, but it was an effective solution for a space we hope to not be needed within a few years.

What we did was a constant balance of this, part of bringing our minds to projects. We saw, obviously, that the current solutions were not adequate but that we also weren’t doing an over-the-top reality TV makeover. Spending too much on one solution would mean the piggy bank would be exhausted for the next place needing a counter. This Ikea-like set that we often defaulted to, is having meals prepped on it in shelters in Przemysl, Jaroslaw, Radymno, and the list grows.

That is the end of my work summary for the November to early January portion of my Poland stay. I’ll do another post talking about the last, and second to last projects I helped with, some more stories of the people I met and worked with, and maybe some general views of Poland and my time at a Polish language school.

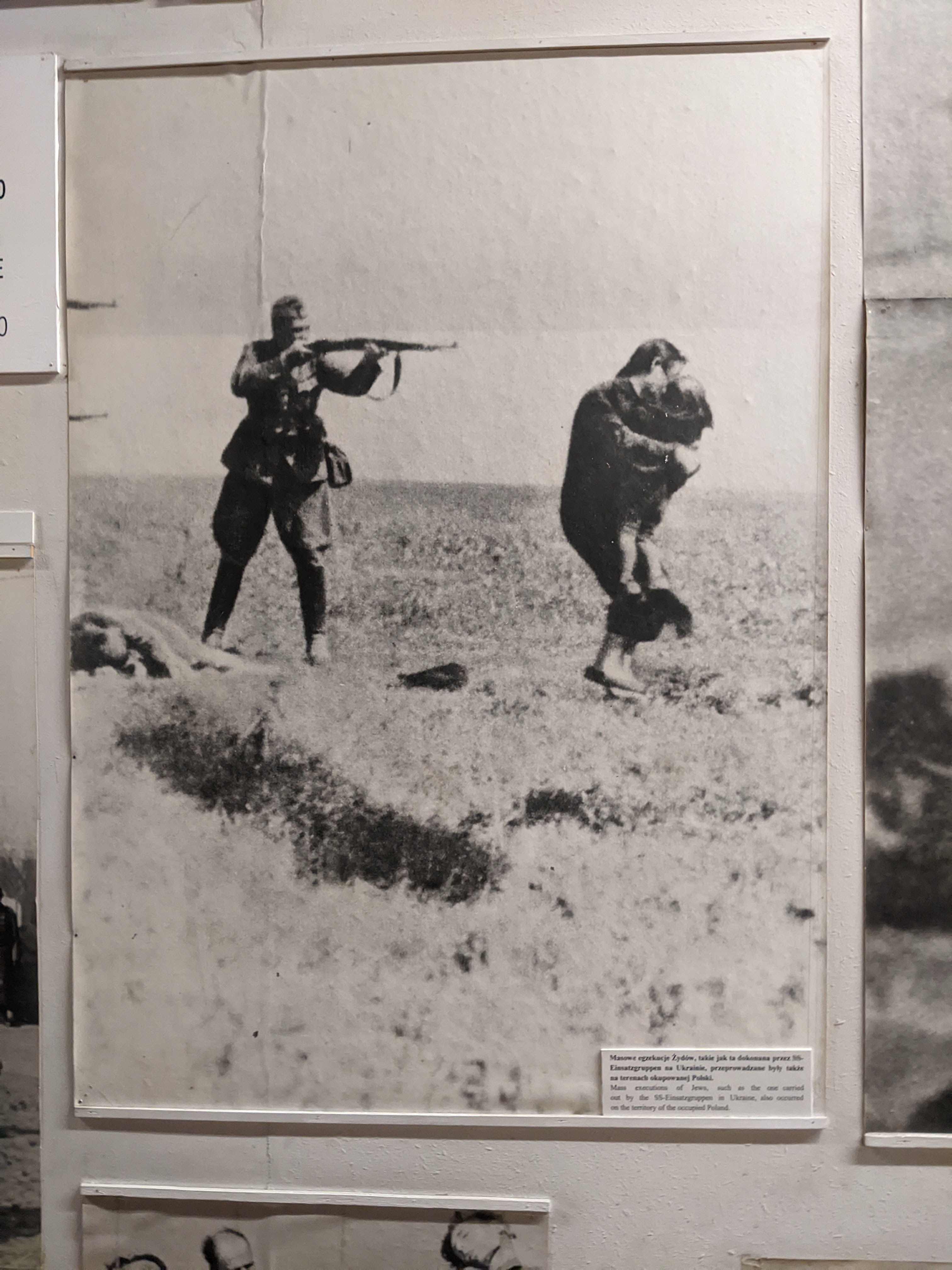

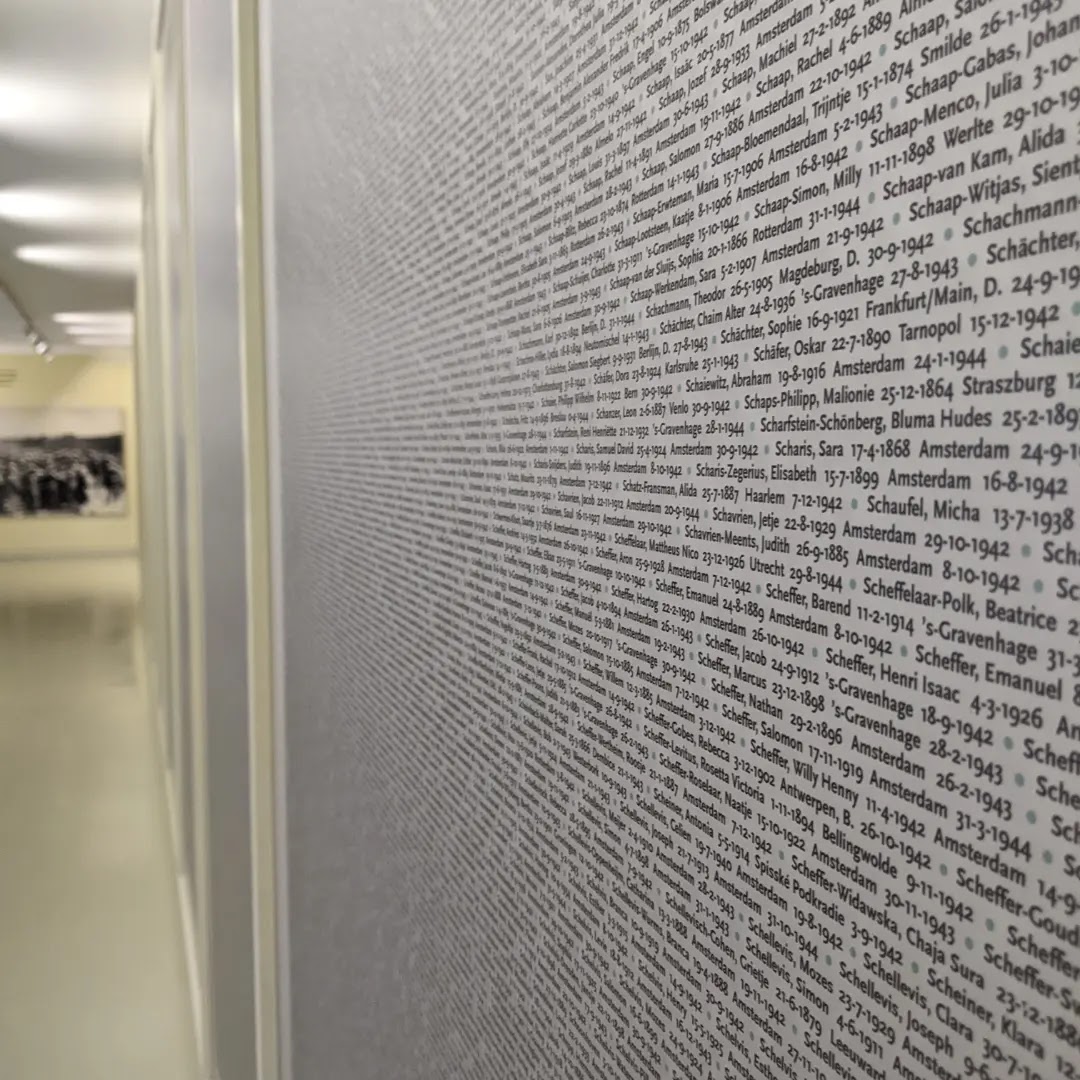

On a far more somber note, I’m going to talk about my visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp. I am not going to use euphemisms or soften what happened there. I will be describing it in clear terms. It’s not to be sensationalist but it’s to speak clearly and plainly, so that any of you who choose to continue reading (and it is a choice,) can confront it for what it was, understand it for what it was, and understand that it’s repeatable if we don’t see its origins clearly.

It’s a horror that we say “can never be” repeated, but already has been. Confronting this aspect of human nature, and learning to combat it, is as important as it’s ever been. Parallels on a smaller scale have already occurred in Ukraine, and further horrors were planned when the full-scale invasion started in February 2022.

I was able to visit Oświęcim (ohsh-WYEN-tsim) on a wet, cold day in December. It’s better known outside of Poland by the German version of its name, Auschwitz. It’s just a small town in Poland, that first had a Polish Army Barracks, which was then turned into a POW camp by the Germans, when Germany and the USSR conspired to tear Poland apart between the two of them. That POW camp evolved into a processing center for nearby labor camps. Increasingly, the “selection” process of choosing who would work, and who would die nearly immediately in nearby gas chambers, became far less selective- overwhelmingly immediately murdering the people arriving by train. Jews and Gypsies and other people demonized by Hitler’s ideology were sent here, from around the territories controlled by Germany.

Compared to exile, imprisonment, or execution, it was considered fairly benign to send “wrongheaded” people of all kinds to labor for several weeks or months, where structure and honest living would reform them. By hijacking this idea, Nazis were able to create a politically acceptable story to what they started to do to German dissidents, then Jews, and Roma, and more and more people.

Similarly, in times of war, it’s not uncommon for national minorities to be mistrusted to key military positions, or any military positions- so a compromise is made. Politically untrustworthy minorities are expected to contribute to the national effort by taking part in mandatory wartime work. By exploiting this kind of expectation, labor camps could be started- while hiding the horrifying truth of how work safety laws were non-existent or ignored. Neglect eventually morphs to abuse- and abuse may morph into direct murder, and eventually systematic murder. The cultural evolution, if it can be called that, of German labor camps, was thus. People tolerated each incremental step.

In Auschwitz, it started with housing thousands of Polish Army prisoners as a POW camp. By the end of operation, it had been the place of murder for over one million people.

This chamber, and the grounds I’ve shown, are of Auschwitz Camp I. The German government decided that it was not a large enough operation to handle what they were planning, and built an expansion one mile away, with even larger chambers and crematoria, and with a railroad expansion to shorten distance from train to chamber. Over 800,000 people were murdered by gas chamber between these two camps alone. As mentioned earlier, total death toll between all these camps reached roughly 1.1 million people.

I wasn’t sure how to end this post, so I’ll leave as is. As I left the museum and headed to Krakow, my travel buddy and I were in shock and struggled to have much to say as we rode the train. There were many exhibits where it was prohibited to take photos and you can still feel surrounded by the thousands of faces.

Leave a comment